Was This Swedish Immigrant the First Continental Divide Thru-Hiker?

Posted by Barney Scout Mann on 28th May 2020

Before applying paint, Peter Parsons traced the letters on the back of his canvas rucksack. He wanted the 3-inch-high text to be perfect—no botched lines made by an excited hand. Parsons painted neatly inside the lines, making block letters that read: HEADING “NORTH”—MEXICO TO CANADA. Parsons intended to hike the Continental Divide.

On a one-cent postcard, he’d just written his best friend, “I’m raring to be on the trail again.” Of course, he used the word “trail” loosely. The year was 1924, and there was no established trail leading from where he was starting to where he was going.

Two days into his trek, in southeastern Arizona, Parsons camped on a parched plain 40 miles north of the Mexico border. With smoke tendrils rising from a mesquite and chaparral cookfire, he opened his loose-leaf journal to a blank page and sharpened his pencil with a sheath knife. Preparing for this journey, Parsons had jammed that blade down onto a grinding wheel. In penmanship fine as the pencil tip, his journal noted the result: “Weight of original knife 3.5 oz, as modified 2.5 oz.” He anticipated toothbrush cutting by more than half a century.

At age 35, Parsons had a lean, hard-muscled mill worker’s body. Still, at 5 feet 8 inches and barely 135 pounds, he knew that ounce-counting mattered. Even with the knife-grinding, his 1920s gear meant that his canvas rucksack weighed more than 60 pounds.

Parsons had experience hauling a heavy load great distances. The previous year, on his first attempt at what we now call a thru-hike, he set about walking 1,300 miles from central Oregon through California’s Mojave Desert, covering half of today’s Pacific Crest Trail by piecing together existing routes and cross-country hiking. In near-ideal conditions, Parsons traversed the Cascades and the Sierra Nevada. But at the Mojave’s edge, he faltered. After a full day of bone-dry creeks and springs, Parsons wrote in his journal, “It’s best to give up.” Hard words for him.

Since arriving in Oregon in 1909, the native Swede had explored plenty of peaks and distant horizons, but the premature end to his hike through Oregon and California was his first setback. Did that episode compel him to aim for an even more audacious goal the following year? And not only to plan it, but to paint it on his pack? Modest by habit, Parsons tended to downplay difficulties. But he’d not only just set himself a seemingly impossible task—he’d also made sure every stranger he met would know it.

I’ve hiked the Divide, Mexico to Canada, and even when I did it, on the Continental Divide Trail in 2015, many called it the toughest long trail in the Lower 48. Parsons never trumpeted his goals, so what made this time different? Here’s my theory, based on my own experience as a hiker, and after getting to know Parsons through countless hours poring over his journals: accountability. A long hike is as much a mental game as a physical challenge—I believe Parsons wrote on his pack for himself, not caring what others would think. The sign would be his constant reminder. In the absence of a family and friends network—and with zero social media providing moral support—Parsons’s pack would cheer him on.

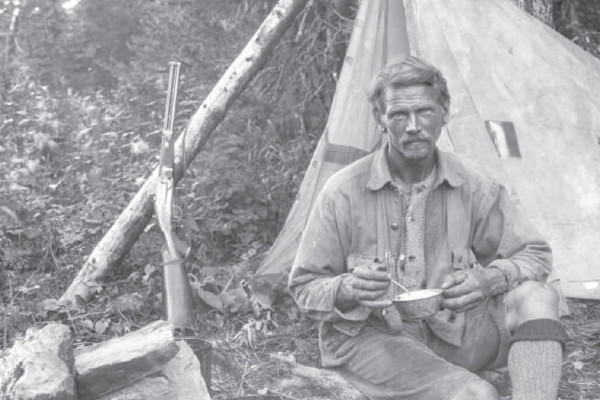

Parsons had propped up his A-frame tent with branches and splayed his outfit around him: rifle, pistol, hand ax, field glass, .22 and .44 caliber ammo, frying pan, two pots, quilted wool sleeping bag, folding Kodak camera in a leather-snap case, metal canteen, compass, soap, sheath knife, journal and pencil. His grub bag, as he called it, was stuffed with rice, beans, flour, peanuts, raisins, and bacon.

He was so joyful to be on his way to Canada that, earlier in the day, he’d hiked barefoot to better feel the desert terrain beneath his feet. Now he recorded his progress in his journal, in right-slanting cursive script. Parsons’ school-book-neat words flowed margin to margin, dodging the circle gaps made for the three-ring pocket binder.

April 13, 1924. Diary—On my hike from Mexico north along the Rocky Mountains: I left Douglas, Arizona yesterday at 1:00 pm and headed north … Today I made about 23 miles.

Was Parsons America’s first border-to-border thru-hiker? His proposed journey upended everything I knew about long trail history. For students of these paths, there are a few accepted facts about the early years. Earl Schaffer walked the Appalachian Trail end to end in 1948, knocking off what is commonly regarded as the world’s first thru-hike. In 1970, Eric Ryback claimed the first Pacific Crest Trail thru-hike, and two years later, Ryback completed the Triple Crown, notching the first transit of the Continental Divide Trail from Mexico to Canada (even 50 years after Parsons, Rybeck found the CDT more a concept than a trail). I’m a Triple Crowner myself and I’ve written books about the PCT and CDT. The New York Times dubbed me the “unofficial historian of the trail.” So it took a shocking discovery to make me question this thru-hiker history.

Ten years ago, I was doing background research for a PCT article at the Mazama’s Mountaineering Club’s archives in Portland, Oregon, when an archivist I’d befriended brought out a near century-old Mt. Jefferson summit register. I couldn’t believe what I read inside. The text suggested that someone set out to hike the Continental Divide in 1924. I did a triple take. 1924! “That’s absurd,” I whispered in the library silence. The register was signed: Peter L. Parsons.

Who was Peter L. Parsons? Was he an empty braggart? Had he made it to Canada? I spent eight years hitting dead-ends. Peter Parsons is a common name, it turns out. I even found a Peter L. Parsons whose headstone had mountains, deer, and trees etched into it; but that Parsons would have been just 15 years old in 1924. The quest felt like looking for El Dorado, the lost city of gold. Was he even real? Had he kept a journal? If so, had it survived? Then two years ago, the North Santiam Historical Society gave me an essential clue: Parsons had a best friend named Otto Witt.

Parsons and Witt arrived in America together. In 1909, the two were shipmates, working on a four-masted freighter sailing from Germany to Oregon. Parsons and Witt were both 20 years old and fleeing dismal prospects in Sweden and Germany, respectively. Witt had aroused the ire of the freighter’s violent captain and the pair jumped ship in Portland, Oregon, rather than completing their contracted journey back to Europe.

They stole down the gangplank and headed south on foot through the Willamette River Valley. After dodging rain and sleeping in sheds, on the third morning they were arrested for trespassing and landed in the county jail. In court they pleaded in broken English, “Judge, we need work.” They were sent packing with a note to Hammond Lumber. A day later, in Mill City, Oregon, a canyon cleft in the foothills of the Cascades, Parsons and Witt went to work for $2 a day.

The two soon fell into a pattern. Parsons would work in the lumber mill for a few months at a time and give the money to Witt, who served as his personal bank. Then Parsons would take off, exploring the Oregon Cascades and beyond. In 1915, he helped erect the first fire lookout on Mt. Hood. He also made jaunts to Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, and Yosemite. On most every journey he kept a journal. He entrusted these records to Witt when he returned, then set out to create more. During two extended leaves, Parsons expanded his résumé with mini careers. He trained and served as a ship-board wireless radio operator. He joined the U.S. Army Air Corps for a brief period. For two winters, Parsons ran traplines in the Alaskan wilderness. But he always came back to hiking, and in 1923 he made that Oregon to Mojave trek.

Each time Parsons left Mill City, Witt received a regular string of letters and penny postcards. These missives were Parsons’s tether to home, such as it was. The pair wasn’t sentimental, but Parsons often opened with “Dear Friend Otto,” and ended with “Otto, get busy and send me a letter.” Parsons wasn’t one to be tied to anything, but his link to Witt was unshakable. The pair jumped ship together, worked together, lived together. Witt always kept a room open for Parsons, sent Parsons money on the road, and safeguarded Parsons’s things.

Witt faithfully stored Parsons’s journals and negatives for more than half a century. And that was no small thing. Over the years, Parsons created a thousand pages contained in a dozen three-ring binders, two scrapbooks, and more than 700 negatives, each individually stored in a glassine wrapper. Witt kept all this safe until he died at age 96, and then his only child, Ursula, became the caretaker. I found her in Longview, Washington, in December, 2017. She was 90 years old at the time and, like her father, had kept Parsons’s records for decades. This was one physical way she could honor the memory of her father—taking over the preservation of something he found so valuable.

The day I entered Ursula’s home, she had laid the journals and negatives neatly on the dining room table. Ursula was excited, even giddy. All this time she’d kept these things, and now someone was telling her they were important. She’d spent half of Christmas Day pulling everything out of the basement.

Did Parsons really undertake a Mexico to Canada hike along the Continental Divide half a century before the trail was even named? Did he finish? The answers were here.

In mid-April, when the sun came out between the rain showers and snow flurries, Parsons tied a white-starred red bandana over his head. Brown hair peeked out over his ears. His prominent cheek bones narrowed quickly to a cleft chin, which together with deep-set blue eyes, made him always look simultaneously intent and curious. His grub bag grew lighter as he plowed through Arizona’s 9,000-foot Chiricahuas and New Mexico’s Big Burro Mountains. When Parsons descended into Silver City, New Mexico, at the end of eight days, he’d covered 175 miles.

In the desert, the ever-curious Swede carved up his first prickly pear. He bit the pink flesh and tasted a blissful hint of watermelon. But then he exploded. “Prickers!” He might just as well have bit a pincushion. “Boy, I learned a lesson,” he wrote. “From now on, I’m sticking to shooting game.”

Just days out of the desert, his metal canteen was icing over as low valleys yielded to mountains. Despite deep snow drifts on the ridges, he was happy to reach the high country. On his first night in alpine terrain, he journaled: “There may be charms to the plains, but it’s the mountains for me.”

If the Continental Divide’s ever-deepening snow worried him, Parsons didn’t write about it. He was not one to complain. He simply wrote, “I have a rough stretch of cross-country ahead,” like a dispassionate reporter. And one night camping next to New Mexico’s treacherous Gila River he wrote: “I don’t know where I am at but it doesn’t really matter.”

Parsons may have understated challenges himself, but those around him had no such reservations. He was in Jemez Springs, New Mexico, when he first heard someone declare that his journey was impossible. When he passed through the small outpost, folks read the words on his pack, shook their heads, and warned: Can’t be done. Jemez Springs sat at 6,198 feet and the two mountain ranges he faced, the Jemez and the San Pedros, were thousands of feet higher. They were remote, steep, and buried under snow. If he encountered trouble, alone, there was no chance of rescue. It was April 26, two weeks into the trek. He’d covered more than 350 miles. He wrote: “I will try it tomorrow.”

What compelled Parsons to forge ahead? What inspired him to undertake a journey that no one else had even imagined? In the same way he downplayed risks, he showed no interest in giving voice to his inner feelings. His journal described wildlife, weather, geology, the pictures he took and the terrain he covered, but he never wrote about what drove him.

Still, he left clues. Parsons’s love for Robert Service poems opens a slender window into his soul. In Alaska, Parsons had copied stanzas from Service’s The Spell of the Yukon into his journal. The words embody a spirit any thru-hiker will recognize.

The strong life that never knows harness.

The wilds where the caribou call,

The freshness, the freedom, the farness,

O God: how I am stuck on it all.

Perhaps with these words echoing in his head, Parsons set forth to traverse the Jemez range. Its sentinel, Chicoma Mountain, reaches an elevation of 11,562 feet. Starting at first light, Parsons ascended, plowing through snow on the high passes. The only tracks he recorded in his journal were deer and wild turkey. Two days later, Parsons tersely wrote: “I made 23 miles today and the same yesterday.” He knew not to gloat. He faced mountains higher still and multiple rivers swollen with spring snowmelt.

Five days later in Chama, on May 1, Parsons was once again told his goal was impossible as he prepared to enter Colorado. “Everybody says I cannot get through because of the snow.”

A day later he wrote: “I am camping in Colorado tonight among snowbanks six feet thick at about 10,000 feet elevation.”

Can’t be done. Parsons’s journal recorded more such warnings. Once, after seeking information about the snow-covered trail ahead in Brooks Lake, Wyoming, he wrote, “The oldest guide here says heading north now is impossible.” Parsons of course continued. A few days later, when he asked about fording a tributary of the Snake River near Jackson Hole, another “expert” told him it was impossible to cross. What he wrote in his journal echoed what he’d told Witt 15 years earlier, when considering the dangers of jumping ship: “I’ve a notion to go anyway.”

Can’t be done. Whether spoken or implied by dubious looks, the phrase had never scared Parsons. Except once. It was in 1917, when a doctor had delivered the ultimate message of defeat. “Tuberculosis can’t be beat,” Parsons was told. It was the year Parsons became a U.S. citizen. He marched down to enlist in the Army Air Corps. The examining doctor told the 29-year-old Parsons he had tuberculosis. Today’s equivalent would be stage-4 cancer. Parsons crawled home to Witt. “What do I do, Otto?”

The two were boarding with Witt’s parents, who had come over from Germany. Witt was the quintessential armchair adventurer, glued to the home front but eager to learn about the world’s wilder edges. In an age before television and the internet, Parsons was Witt’s personal Discovery Channel and BACKPACKER Instagram feed.

But both Parsons and Witt devoured books. So when Witt heard Parsons’s pleading question, he gave him a book on health. Parsons read every page. The book said to live outdoors. Parsons bought a tent and put it up in the woods nearby. He followed the book’s strict diet. Slowly Parsons recovered. He went back to work at the lumber mill and within the year he passed the physical exam to enter the Army Air Corps. Forever, he credited Witt with saving his life.

By mid-May, Parsons was well into Colorado, traversing its slab-sided mountains, deep in country where Fourteeners were commonplace. Each time he reached a new pass or ridge, the snow depth felt higher than the last. He wrote to Witt from Walden, Colorado: “I just came down from 3 passes on the Continental Divide where the snow was 20ft in places.” On May 18, sinking to his hips in drifts, Parsons must have wondered if he’d have to abort the trek. But with nearly 900 miles covered, he was already so far along. Then Parsons spotted some abandoned wooden boards. The resilient mill worker knew what to do. With rope, he fashioned a crude set of snowshoes that carried him over the deepest drifts.

This was a classic Parsons move. He was an inventor, a tinkerer, a problem solver. He held a U.S. patent for an improved aeroplane radiator (it never proved lucrative for him). He even cooked up his own bug dope: “3oz pine tar, 2oz Caster oil and 1oz Pennyroyal oil.”

In southern Wyoming, with the mosquitoes swarming, he slathered on the black gooey repellent. He couldn’t help but note, “Maybe some folks will object to the pine tar.”

One Parsons invention allowed him to take selfies long before cameras came equipped with self-timers. I was incredulous when I first saw the negatives. They’d been individually protected in 100-pack folios. One of the first photos showed Parsons, alone, at Fall River Pass in northern Colorado. He stood at 12,000 feet, boots on ribbed, sun-cupped snow. How did he do it? Every photo of himself showed one hand pursed, fingers looking like they’d just clutched a pebble. One scratched negative gave his secret away. Parsons knelt on a rock at the edge of a shallow lake. His hand clutched a string leading back to the camera 15 feet away. He’d made a remote shutter release with twine.

Of course, some of his inventions had mixed success. In Saratoga, Wyoming, Parsons ran into the North Fork Platte River. It bisected the town, running due north, and its speeding water gave him an idea. The next morning, at sunrise, Parsons was up searching for logs and old fencing wire. He fashioned a crude raft with his ax and rope and rode the rocking vessel toward Canada. In swift water, midday, Parsons spotted foaming rapids dead ahead. He knew he’d founder. Abandoning ship, Parsons made a frantic leap, carrying himself and his pack ashore.

Only once did Parsons record any self-doubt. And it was not about his ability to keep moving northward.

On a rainy June day in southern Montana, he hiked into Dailey, a village that no longer exists. At a lunch counter, his numb fingers gripped a warm cup of coffee. A woman came in the door wearing a leather cap with goggles pushed up above her eyes. Her knee-high boots left damp puddles on the floor.

“Today a young lady came along driving a motorcycle,” Parsons wrote. “She was wearing boots, slicker coat and sou-wester. The rain had been beating her face till she was all flushed. She stopped to tie down her sidecar as it was bounding too much empty. I chatted with her after finishing my coffee. She had driven all the way from Philadelphia a few days before. She was the most self-sufficient young woman I had seen for a long time. She was one in a thousand, that I liked right away.”

Parsons never underlined a phrase, but he did this time as his pencil scratched away that evening. He was a mile outside of Dailey, overnighting in a deserted schoolhouse before a comfortable fire. After he finished writing, it’s easy to imagine him holding the journal and re-reading the fresh words. The last line would have cut like his sheath knife: “I have been kicking myself for a silly ass ever since I left her for not getting better acquainted or getting her name and address.”

Parsons never learned her name. But 95 years later, I confirmed that Parsons’s instinct was right. Her name was Margaret Lindsey. She was one in a thousand. She did ride a Harley Davidson from Philadelphia. A year after meeting Parsons in Dailey, Lindsey became the first woman ranger at Yellowstone National Park.

When Parsons passed through Yellowstone, it was a different park than the one we know today in all respects but one: Old Faithful’s crowds. After going days without seeing a soul, Parsons was stunned by the sightseers and felt hemmed in by fences that said Keep Out. Later, only miles away, with impish delight, Parsons cooked dinner by balancing his pot over a steam vent. The roar of geysers was his lullaby that night.

Crossing into Montana, the goal painted on Parsons’s pack no longer seemed so far-fetched. He was in his last state, but it was a big one. Ahead lay the 200-mile stretch of what today is the Bob Marshall Wilderness, and after that Glacier National Park, his final hurdle.

On July 4, after a string of 30-mile days put him within spitting distance of the park, Parsons celebrated by walking barefoot. He strung his boots together and hung them over a shoulder, just like on his second day so many miles ago. This time, instead of being scraped raw by hardscrabble desert, Parsons felt his bare soles caressed. That night he wrote, “I was on trail soft as velvet from half-decayed needles and moss.”

In Glacier National Park, he woke well before dawn to climb Triple Divide Peak. He stood on the summit on the morning of July 8, savoring the geographical anomaly. If water splashed from his canteen it could flow into the Atlantic, Pacific, or Arctic Oceans. Parsons peered north through his field glass. “I’m within a week of finishing,” he wrote.

Monday, July 14, the day dawned to animal encounters. A deer startled Parsons, nearly running over his camp. He saw five grouse, a second deer, and then a waddling porcupine. Rounding a bend, he faced down a large black bear. “It made the fastest Immelmann turn I’ve seen,” he wrote. Parsons kept busy recording the menagerie. But his reference to the main event was spare: “I crossed the Boundary Line at 2:00 pm.” Peter Parsons had made it.

Parsons posed for the Kodak. His pack—with its message now a fact—leaned up against the boundary obelisk. The monument tip was barely higher than his chin. He squinted at the camera, and without bothering to smooth his hair did something not seen in any of his other photos from the hike. He smiled—just a little.

Although he could have been home within days, walking into the second-floor room Witt kept waiting for him, Parsons stayed out five more weeks, unwilling or unable to let the adventure end. By foot and train, he worked his way west in Canada before crossing into Washington. He climbed Mt. Rainier for the heck of it. His postcard to Witt indicated he still had his trail legs: “Yesterday I made the climb to the summit in about half the time it takes ordinary climbing parties.”

Parsons had one last peak to summit before reaching home: Oregon’s Mt. Jefferson. On Rainier he’d merely signed his name in the summit register. On Jefferson, for reasons he didn’t explain, he felt compelled to give a nod to his long hike before signing his name.

“I started a hiking trip from the Mexican border April 12 and followed the Rocky Mountains north to Canada then across to Mt. Rainier then south along the Cascades to here. Four and a half months along the way.”

Ninety years later, this was the summit register entry I read. Finding Parsons’s journals and photos had solved the mystery, but while investigating his life, I learned there was one more riddle. The saga didn’t end with his return to Witt’s house.

After 1924, Parsons continued to work falls and winters and spend summers outdoors. And his ambition as an explorer only grew. Mexico to Canada became Mexico to Alaska. A local newspaper recorded his expanded quest. In 1927, The Democrat of Albany, Oregon, reported: “Peter Parsons of Mill City is leaving today for a continuation of his hiking tour from Mexico to Alaska. Mr. Parsons, a picturesque character and a woodsman of the first degree, started his hiking trip several years ago.” The article stated that Parsons was an expert marksman who depended on his rifle for food, that he didn’t expect to see anyone, and that he was covering ground that was a blank space on the map.

For four summers he pursued this new goal, but the Canadian Rockies proved a formidable challenge. Late snowmelt and trackless forest slowed his progress. Each year’s trek was cut short. In total, he only covered another 600 miles. Nonetheless, Mexico to Alaska became Mexico to the Arctic Ocean, and he persevered. In 1930, he was emboldened by the opportunity to switch from foot to canoe, which promised to greatly increase his pace.

In early June of that year, Witt received a long letter from Peace River Crossing, Alberta. Parsons told his friend that he’d run rapids that everyone said were a terror. Parsons planned to keep going, down the Peace River, past the Rapids of the Drowned, to the Great Slave Lake and then down the McKenzie River to the Arctic Ocean. Parsons was excited. He’d just covered 550 river miles in two weeks. He had 3,500 more to go.

Parsons gave Witt his bank account number, just in case, but closed on a hopeful note, suggesting he just needed to finish this final feat before coming home. Write soon, Parsons finished. “I close for this time with the best regards.”

Two months later, Witt received another letter. It was from the Alberta Provincial Police. Parsons’s body had washed up near the Rapids of the Drowned. He was found 800 miles downstream from Peace River Crossing. Witt’s address was in his wallet.

Puzzles surrounded Parsons’s death. His body was found more than a month after he’d died and it was found just above the rapids, not below them. His wallet had not been taken, but his rifle, which he’d customized, was briefly seen later for sale in Uncle Ben’s Store in Edmonton. When the friend who saw it went back to ask questions, the rifle had disappeared. Had Parsons’s long string of luck simply run out or had there been foul play? There’s no record of any investigation.

Even in death, Parsons delivered one more surprise. Eighteen months after he died at the age of 42, two Rocky Mountain ski pioneers set out to make the first winter ascent of Canada’s Mt. Resplendent. Their last stop before the big push was a deserted log cabin at the base of the 11,237 foot mountain. There, they found this message carved into the cabin’s wall: Be it hereby recorded that on this day, February 28, 1930, I went up along the Robson glacier to the top of the Divide on skis …. from there I continued to the summit of Mt. Resplendent on foot. Peter L. Parsons.

Despite all of his record-setting exploits, the legend of Peter Parsons faded in the following decades. He was forgotten everywhere but the Witt household, where Parsons lived on in the stories Otto told his daughter Ursula. Every time Witt’s tales tapered off, he ended the same way. He would grow wistful as he finished and then he’d look far away, and tell Ursula, “Pete Parsons would have hated growing old.”

A Note for Purists: Thru-hikes are long and not easily verified, so every claim of a “first” thru-hike is scrutinized. People ask, “Did they hike it all?” In Parsons’s day there was no CDT, only the next ridge ahead on the Divide. He squared off most of today’s mile-adding bends. Parsons pieced together prospectors’ trails, old mine and timber tracks, railroad rights of way, long lengths of cross-country, and road-walking on two-lane highways. He was capable of 30-mile days and strung many together. But he never claimed to be a purist. He did ride his raft for half a day. He did take the occasional ride. He described one five-day stretch in a postcard to Witt: “I covered 175 miles, although I rode about 25.” Considering the era, the conditions, and his gear, I won’t be splitting hairs. –B.S.M.

Written by Barney Scout Mann for Backpacker and legally licensed through the Matcha publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@getmatcha.com.

Share on: